Black voters have

voted en masse for the Democratic Party since the mid-60s and the

passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act and the

social welfare programs of the Great Society. This solidified black

voters behind the Democratic Party, but they had been moving there since

the New Deal.

However, it’s a historical anomaly in the United States. The traditional

home of the black voter was the Republican Party, due to its historical

role in ending slavery and introducing Reconstruction Acts and

Amendments to the Constitution. It also did not help that the Democratic

Party was the party of Jim Crow, a system of legally enforced

segregation present throughout the American South in the aftermath of

the Civil War.

What Do We Mean When We Say “Jim Crow?”

Before delving further into the topic, it is important

to define precisely what we mean by Jim Crow and why it is a distinct

form of legal codes in United States history. While Northern and Western

cities were by no means integrated, this integration was de facto, not

de jure. In many cases, the discrimination in the North was a

discrimination of custom and preference, discrimination that could not

be removed without a highly intrusive government action ensuring

equality of outcome. Northerners and Westerners were not required to

discriminate, but nor were they forbidden from doing so.

Compare this to the series of laws in the American South known for

mandating segregation at everything from public schools to water

fountains.

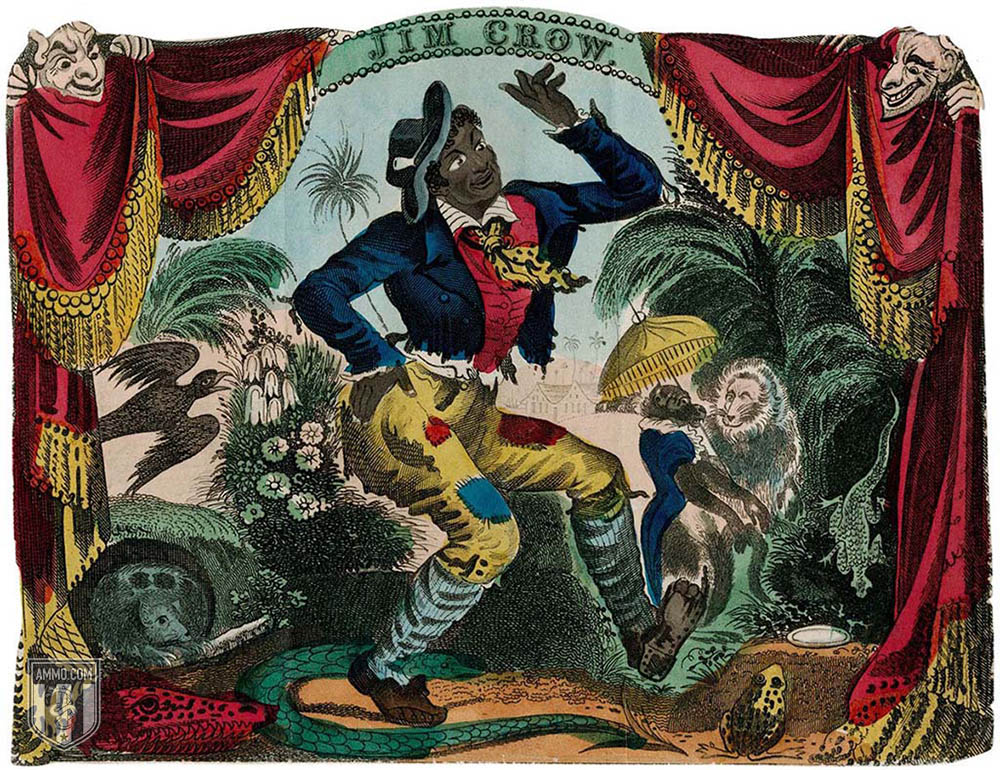

No one is entirely sure where the term “Jim Crow” came from, but it’s

suspected that it comes from an old minstrel show song and dance routine

called “Jump Jim Crow.” Curiously, the first political application of

the term “Jim Crow” was applied to the white populist supporters of

President Andrew Jackson. The history of the Jim Crow phenomenon we are

discussing here goes back to the end of Reconstruction in the United

States.

The Reconstruction Era

Briefly, Reconstruction was the means by which the

federal government reasserted control over the Southern states that had

previously seceded to form the Confederate States of America. This

involved military occupation and the disenfranchisement of the bulk of

the white population of the states. The results of the Reconstruction

Era were mixed. Ultimately, Reconstruction ended as part of a bargain to

put President Rutherford B. Hayes into the White House after the 1876

election. The lasting results of Reconstruction are best enumerated for

our purposes as the Reconstruction Amendments:

- The 13th Amendment abolished involuntary servitude for anyone other than criminals. It was once voted down and passed only through the extensive political maneuvering on behalf of President Abraham Lincoln himself and the approval of dubious Reconstruction state governments in the South. It became law in December 1865.

- The 14th Amendment includes a number of provisions often thought to be part of the Bill of Rights, such as the Equal Protection Clause and the Due Process Clause, which are, in fact, later innovations. Birthright citizenship’s advocates claim that the Constitutional justification can be found in this sprawling Amendment, which also includes Amendments barring former Confederate officials from office and addresses Confederate war debts. This Amendment became law in July 1868.

- The 15th Amendment prevents discrimination against voters on the basis of race or skin color. This law was quickly circumvented by a number of laws discriminating against all voters on the basis of income (poll tax) or education (literacy tests). The Southern states eventually figured out how to prevent black citizens from voting while allowing white ones through grandfather clauses.

- The Reconstruction Amendments were the first amendments to the Constitution passed in almost 60 years, and represented a significant expansion of federal power.

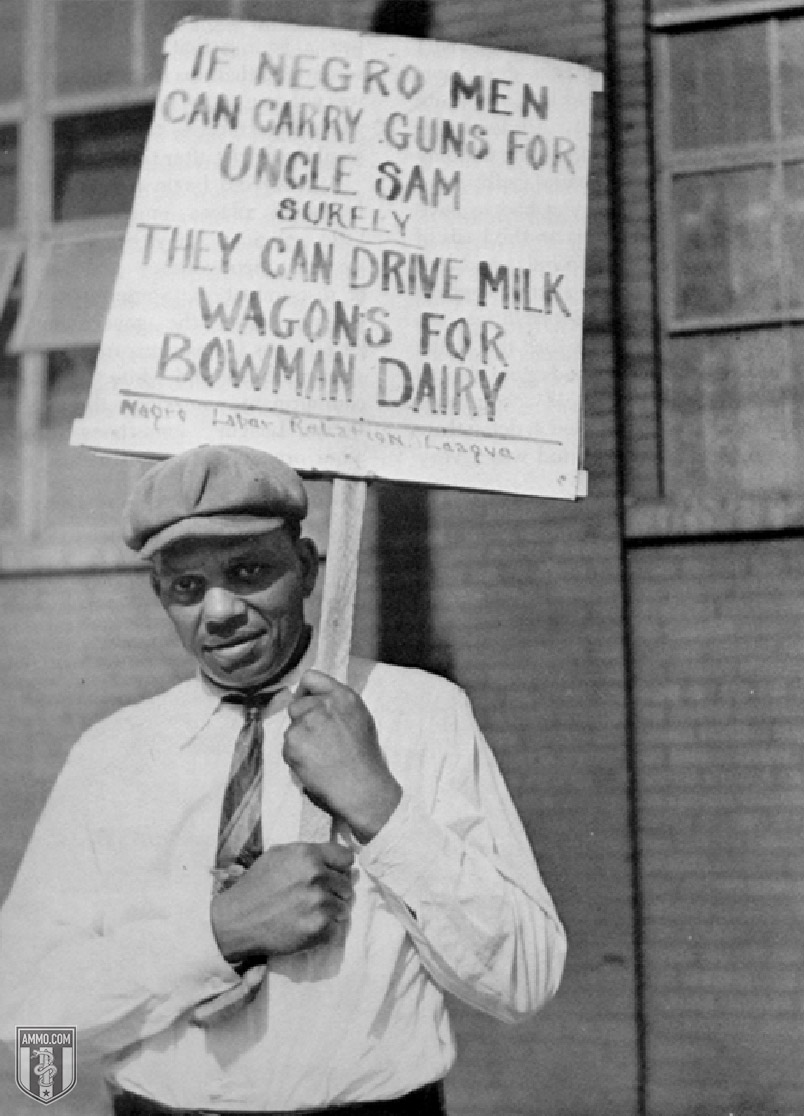

Black Disenfranchisement as a Prologue to Jim Crow

The process of black disenfranchisement at the end of the war is important historical context for understanding the rise of Jim Crow. It’s impossible to discuss this period without discussing the role of the Ku Klux Klan and other Democratic Party-allied white supremacist terrorist organizations. You can read more about this in our lengthy and exhaustive history of American militias and paramilitary organizations.

The first attempt to roll back the gains made by black Americans, thanks to the Reconstruction Amendments, was a poll tax introduced by Georgia in 1877. However, the legal rollback of voting rights in particular did not really ramp up until the turn of the century, when Republicans ran on joint tickets with the insurgent People’s Party, also known as the Populist Party. This threat to entrenched Democratic Party political power (and all of the patronage that came with it), while certainly related to the racial question, was arguably a bigger motivator than race. In many cases, such as with poll taxes, there were explicit attempts to exclude white voters sympathetic to the Republican cause alongside black voters. The specter of unity between poor blacks and poor whites loomed large.

Mississippi drafted a new constitution in 1890, which required payment of a poll tax as well as the passing of a literacy test as qualifications to vote. This passed Constitutional muster in 1898, with Williams vs. Mississippi. Other Southern states quickly drafted new constitutions modelled on that of Mississippi. This was known as “the Mississippi Plan.” By 1908, every Southern state had either drafted a new constitution or passed a suffrage amendment to better craft the state electorate to their liking. In 1903, Giles vs. Harris strengthened federal court support of such laws.

Another method of maintaining control was the white primary. In 1923, Texas became the first state to establish primary voting for whites only. This was quickly deemed unconstitutional, so the state simply drafted a new law saying that the Democratic Party could determine its own voters for the primary. The state party quickly moved to exclude all non-white voters, which was entirely legal and Constitutional, because the Democratic Party was a private organization.

This caught the eye of some Congressmen. By 1900, there was discussion of stripping Southern states of some of their Congressional representation in accordance with provisions contained within the Reconstruction Amendments. Not only was the “Solid South” a large voting bloc, due to the one-party nature of many Southern elections, but they were also in charge of a goodly number of committee chairs, meaning that any attempt to strip Southern states of seats was probably going to go precisely nowhere.

Reliable statistics from the era are few and far between, but historians believe that somewhere between one and five percent of eligible black voters were registered by the late 1930s. Very few of these actually voted in general elections, which were a foregone conclusion. In many states, prior to the first and second Great Migrations, the black population ranged upwards of close to 50 percent.

Five border states (Delaware, Maryland, West Virginia, Kentucky and Maryland) all attempted to pass similar legislation to “the Mississippi Plan,” but failed to do so.

Redeemer Governments and the Election of 1876

The disenfranchisement of black Americans in the South

was the political precursor for Jim Crow. In addition to legal

disenfranchisement, there were also paramilitary actions against both

black Americans and Republican voters and candidates. It was not

uncommon for Democratic Party-allied paramilitary groups to simply force

the Republican candidate or even office holder out of town. Voter fraud

was also a tool. As elections became closer, violence against blacks

and Republicans increased to keep them away from the polls.

These Southern governments are known collectively as the Redeemer

governments. They ruled over most of the South from 1870 until 1910. As

we discuss in our history of militias in the United States, the white,

pro-Democratic Party militias of the South were largely obsolete by the

end of the 19th Century – Democratic Party state governments were doing

their jobs for them.

All of this was facilitated by the Compromise of 1877 or the Corrupt

Bargain of 1877, depending on one’s point of view. In exchange for

certifying Southern votes for Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes,

Hayes agreed to:

- Remove federal troops from Florida, South Carolina and Louisiana, the final states where they remained. Hayes campaigned on doing this prior to the bargain.

- The appointment of one or more Southerners to the Hayes Cabinet. This was fulfilled by appointing David M. Key from Tennessee as the Postmaster General.

- A transcontinental railroad passing through the South, using the Texas and Pacific line.

- Legislation to industrialize the Southern economy.

- Northern hands off the South when it came to racial questions.

- The first two are often emphasized, however, they are probably the least important parts of the compromise. As stated above, Hayes had already planned to withdraw the remaining troops from the South. The cabinet appointment of Postmaster General was certainly a bigger deal than it would be today, when far fewer people rely upon the mail. The post has not even been a cabinet-level position since the 1970s. The next two are arguably beneficial to everyone in the South, black or white, and in any event, were never enacted.

The final provision, however, is the one that makes Jim Crow possible. This makes it, historically speaking, perhaps the most significant of the Compromise provisions.

The Democratic Party Coup d’Etat in Wilmington, North Carolina

The end of Reconstruction and the subsequent

disenfranchisement of blacks and poor whites by Southern Democratic

state governments were not entirely without resistance. However, this

resistance was met with sharp and swift reprisal. For example, in

November 1898, when the brother of a Republican candidate tried to

collect affidavits from black voters that they were being prevented from

voting, he was savagely beaten by cronies of the local Democratic Party

leader. Four days of rioting followed, including 13 blacks and at least

one white dead and hundreds injured.

The same month and year in Wilmington, North Carolina, there was an orgy

of violence and an effective coup d’etat against the duly elected

Fusionist government (blacks represented by Republicans and whites

represented by Populists) of the city. Here the Democratic Party

explicitly called themselves “The White Man’s Party,” forcing whites to

join political and labor organizations. People were literally marched

out of their homes in the middle of the night and forced to sign

membership forms under threat of death.

Following a speech from former Democratic Party Congressman Alfred Moore

Waddle, Red Shirts in attendance left the convention hall and began

terrorizing black citizens. The eventual election was rife with fraud.

The local black newspaper, The Daily Record, was, along with many others

around the state, burned to the ground. Waddell led a group to the

Republican mayor of the town, forcing him and the entire city council to

resign at gunpoint. The new city council was installed and elected

Waddell as mayor.

The organizer of the coup, Charles Aycock, became the 50th Governor of

North Carolina as a Democrat. Other participants became the first female

Senator (Rebecca Felton), Secretary of the Navy (Josephus Daniels), a

state Senator and U.S. Congressman (John Bellamy), a state Senator and

Governor of North Carolina (Robert Glenn), House Majority Leader and

Ways and Means Committee Chair (Claude Kitchin), Congressman and

Governor of North Carolina (W.W. Kitchin), another Governor of North

Carolina (Cameron Morrison) and a Lieutenant Governor (Francis Winston).

The disenfranchisement leading up to Jim Crow went deeper than simply

stripping the right to vote. It also included removing black citizens

from juries and preventing them from being eligible to run for public

office.

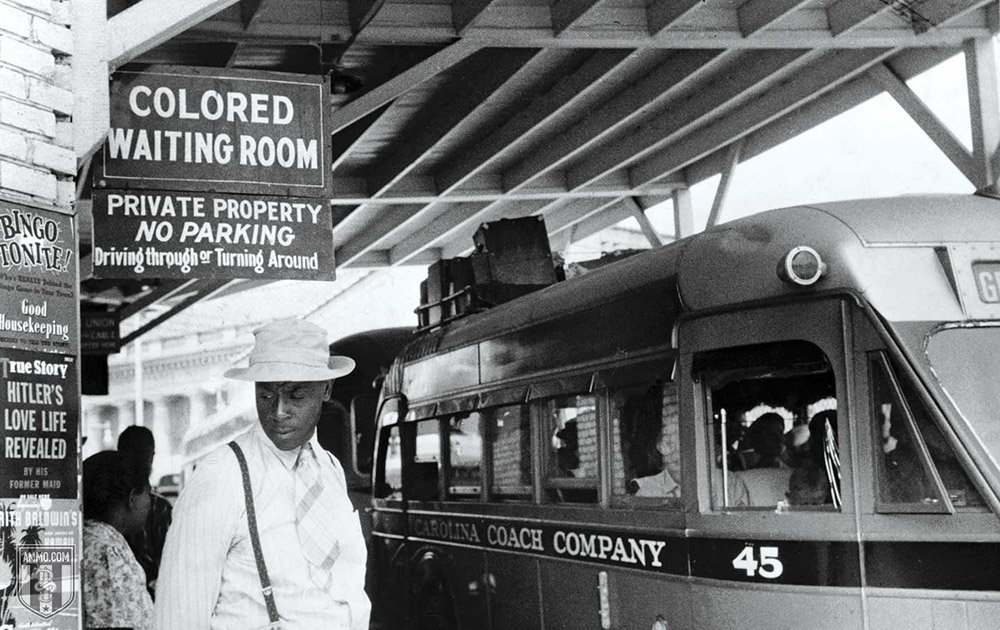

What Were the Jim Crow Laws?

Jim Crow laws, for the most part, are relatively

simple. Most states (over 30), including those outside of the South, had

laws against interracial marriage, a crime known as miscegenation. The

remaining laws against this were overturned by the Supreme Court in

1967, in the Loving v. Virginia case. Some states went further than

this, such as Florida, which banned both interracial dating and

cohabitation. Schools, restaurants, theaters and cinemas, hotels and

train stations were commonly separated by law, but sometimes baseball

teams and prisons were segregated by law, as in Georgia. Mississippi

criminalized anti-Jim Crow propaganda. North Carolina banned the sharing

of books between black and white schools.

The Supreme Court Upholds Jim Crow in Plessy v. Ferguson

The landmark Supreme Court case that upheld Jim Crow

was Plessy v. Ferguson. The law in question was an 1890 Louisiana law

requiring separate train cars for black and white passengers. Homer

Plessy, a mixed-race Louisianan (an “octaroon” – ⅞ white and ⅛ black)

and registered Republican (as most Southern blacks were at the time),

deliberately forced the issue as a test case.

He bought a first-class ticket and boarded the white train car. The

train company knew about this in advance. They opposed the law on the

grounds that it would require them to effectively double the number of

train cars without a corresponding increase in passengers. The committee

looking to challenge the law hired a private detective with arrest

powers to ensure that Plessy would be arrested for violating the train

car segregation law, and not vagrancy or something else.

Plessy and his backers lost every decision on the way up to the Supreme

Court, which upheld earlier court rulings. This led to the doctrine of

“separate but equal.” The legal theory was that public accommodations

must be provided to all citizens, but they could be separate, provided

that they were of equal quality. The argument among critics was that the

separate facilities were never equal.

This was a turning point in the history of American jurisprudence. The

Supreme Court made Jim Crow the law of the land in any state that wished

to do so. It is important to again reiterate what Jim Crow was and was

not. Jim Crow was a state policy demanding segregation from private

business. It was not a law allowing for businesses to discriminate if

they wished to. In this respect, it was like a continuation of the slave

patrols of old, whereby private citizens were drafted into the militia

to hunt for runaway slaves. As we can see above, the private business in

question did not want to enforce the law, if only for purely economic

reasons, but was forced to by the state Democratic Party apparatus.

A lesser known phenomenon of the Jim Crow Era is the Sundown Town. These

were towns where black Americans were simply not allowed to be out

after dark. For the most part, this was overturned when a matter of laws

barring black men from a town or even areas of a town did not pass

Constitutional muster. Some municipalities got around this by appealing

to city planners or real estate professionals.

Democrat Woodrow Wilson: The Segregation President

Democrat Woodrow Wilson was arguably one of the most transformational

presidents in American history. Not only did he pioneer the aggressive

interventionist foreign policy that later came to characterize American

international relations, he was also the segregation president. While he

was previously the Governor of New Jersey, his personal background was

in the American South – Virginia to be exact.

Wilson basically walked into the White House during the 1912 election.

The Republican Party was split between supporters of President William

Taft and former President Theodore Roosevelt, who ran on his own

Progressive Party. Taft all but bowed out of the race. Historians have

argued that he was more interested in his eventual job as Chief Justice

of the Supreme Court than he was in being president. Wilson won 40

states, while the incumbent president won two. TR carried the balance.

The 1916 election was much closer in the popular vote, with Wilson eking

his way to victory in what was effectively a referendum on whether or

not the United States would enter the Great War on the side of Great

Britain.

Ironically, Wilson was the dove in the race.

(Once in power, Wilson’s dovish outlook led him to change American

foreign policy. He argued against using self-interest as a basis for

foreign alliances and instead said foreign policy should be based upon

collective security and moral judgement. He led the creation of the

League of Nations, the precursor to the United Nations.)

Wilson was the first Southerner to occupy the White House since fellow

Virginian Zachary Taylor in 1848. While some have argued that the

so-called “Nadir of Race Relations” in America was either earlier or

later than Wilson, it’s hard to not see the Wilson Administration as a

turning point and consolidation of segregation on a national scale.

Segregation at the federal level became the law of the land under

Wilson. While Wilson rejected proposals to segregate every department,

he allowed cabinet heads to segregate their own departments as they

wished. The military segregated, with all-black units serving underneath

white officers at equal pay. The First Great Migration led to a number

of race riots and the Wilson Administration did not intervene under the

advice of his attorney general.

It’s worth noting that Wilson personally shared the “Lost Cause” view of

the War Between the States. He also saw the Redeemer governments as an

understandable response to radical Republican rule. Neither of these

views are particularly controversial nor, in and of themselves, racist.

However, they are worth bringing up due to Wilson’s role as the most

segregationist president since the end of the Civil War.

The Wilson Era was also the period of the resurgence of the KKK and the

popularity of the film The Birth of a Nation that Wilson showed in the White House.

The summer after Wilson left the White House was known as “Red Summer,”

due to the number of race riots. Over 165 people were killed. All told,

there were 39 race riots throughout the United States between February

and October 1919. The African Blood Brotherhood was formed for the sake

of black self defense during this period, but was quickly taken over by

the nascent Communist Party.

Jim Crow Begins to Fall Apart

After the Second World War, however, the system of

segregation began to show cracks. Northern liberals in the Democratic

Party, such as Hubert Humphrey, were unwilling to continue to look the

other way. President Harry S. Truman, a Democrat from the border state

of Missouri, made inroads against segregation. He appointed the

President’s Commission on Civil Rights, which drafted a 10-point plan to

advance civil rights.

Part of the change in racial relations had to do with the service of

black Americans during the war. Truman himself said "My forebears were

Confederates...but my very stomach turned over when I had learned that

Negro soldiers, just back from overseas, were being dumped out of Army

trucks in Mississippi and beaten." Truman aggressively pursued a policy

of integration and fairness in the military and federal employment,

banning racial discrimination in civil service.

There was, of course, a predictable backlash. Southern Democrats were unhappy with Truman’s actions on civil rights. They became known as the "Dixiecrats" when they split from the party in 1948 and formed the States’ Rights Democratic Party. It met in Birmingham, Alabama. On July 17, 1948, they nominated then-Democrat Gov. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina for president and Gov. Fielding L. Wright of Mississippi for vice president. They even managed to secure a place on the main Democratic Party line in four states, all of which Thurmond won. The only non-Confederate states where Thurmond appeared on the ballot were Kentucky, Maryland, California and North Dakota.

The Dixiecrats carried South Carolina, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama. They received 39 electoral votes and about 1,000,000 popular votes. After their failed 1948 election attempt, the splinter party dissolved and the members returned to being part of the Democratic Party.

Curiously, Thurmond was considered something of a progressive during his tenure as Governor of South Carolina. He personally fought for the arrest of the men who lynched Willie Earle. While no one was ever convicted for the crime, Thurmond was personally thanked for his efforts by the NAACP and the ACLU.

The purpose was not to win, but rather to force the election into the House of Representatives where, it was thought, the Dixiecrats could force concessions from either President Truman or New York Governor Thomas Dewey.

Thurmond fought a vigorous campaign, challenging President Truman to a

debate on the civil rights question. He claimed until the day he died

that the impetus for his campaign against civil rights was not based on

racism, but on opposition to Communism. After the campaign, the original

plan was to continue the States Rights’ Democratic Party as an

alternative to the regular Democratic Party, but it fell apart when

Thurmond realized he could not fully abandon the party.

Jim Crow began to fall apart completely in 1954, with the landmark

Supreme Court decision Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka. At the

time of the ruling, 20 states forbade racial segregation in public

schools, with another three making it optional or limited. Only in the

old Confederacy as well as Oklahoma, Missouri, Kentucky, West Virginia,

Maryland and Delaware was it mandatory.

This was not the end of the story. Democratic Party state governments

and politicians, led by Virginia’s Sen. Harry Byrd, coordinated a

campaign of “massive resistance.” In some municipalities, public schools

were shuttered entirely rather than allowing black children to attend

school there. This led to the rise of the segregation academy, private

schools exclusively for white students, which continued legally until

1976.

A series of bills passed between 1957 and 1965 meant that segregation

was all but over, except for the shouting. The first, the Civil Rights

Act of 1957 signed into law by President Dwight Eisenhower, was championed by Illinois Senator Everett Dirksen with the support of future President Lyndon Baines

Johnson who was at that time the most powerful figure in the United States

Senate. Strom Thurmond tried to block it with the longest one-man

filibuster in history – 24 hours and 18 minutes. The bill sought to

secure voting rights and was largely ineffective.

The Civil Rights Act of 1960 followed, further seeking to strengthen

minority voting rights in the Southern states, as well as to reinforce

desegregation. The Civil Rights Act of 1960, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of

1965--all championed by Senator Dirksen--along with the Brown v. Board decision, can be seen as the

effective end of Jim Crow legislatively.

It is worth noting that Wallace’s own support for segregation might have been entirely opportunistic. He initially ran for Governor of Alabama as a pan-racial populist. After losing, he declared, “I will never be outn*ggered again” and later reflected that, "You know, I tried to talk about good roads and good schools and all these things that have been part of my career, and nobody listened. And then I began talking about n*ggers, and they stomped the floor." Wallace, like Thurmond before him, sought to throw the presidential election to the House.

Wallace was, at the time, Governor of Alabama. He had previously run for President in 1964 as a Democrat (as he did again in 1972), but this time he ran as the standard bearer of the American Independent Party. His unofficial slogan was “there’s not a dime’s worth of difference between the two major parties.” He ran on a law-and-order and pro-segregation platform seeking to, as Thurmond did before him, throw the election to the House.

Wallace was arguably far more successful than Thurmond. First, he got 46 electoral votes to Thurmond’s 39, making him the last third-party candidate to get electoral votes. He also got nearly 10 million votes (9.9 million) compared to Thurmond’s 1.1 million. For Thurmond, this was a scant 2.4 percent of the vote, compared to Wallace’s 13.5 percent. While Wallace ran first in the Confederacy with 45 percent of the vote, he succeeded where Thurmond did not, for making a direct appeal to Northern working-class voters. Fully one in three AFL-CIO members supported Wallace in the summer of ‘68. In September of 1968, Wallace was the preferred candidate of Chicago steelworkers, taking 44 percent of their support.

Soon-to-be President Richard Nixon, however, with the help of a young Patrick Buchanan, turned the tide. Nixon argued that a vote for Wallace was ultimately a vote for Humphrey. He also hammered away at Alabama being a right-to-work state. While it is often argued that Nixon pursued a “Southern strategy,” this is patently false. Nixon’s strategy was two-fold: He sought to win on the basis of massive turnout from Northern Catholics and Southern Protestants, the latter category including Southern black voters.

There is a solid argument to be made that the Democrats are still the party of racism, but that the focus of their racism has moved from blacks to working-class whites. Governor Andy Beshear has promised to provide healthcare to all blacks in the state of Kentucky – no word on what he’s doing for impoverished whites in the state, which “boasts” a 16.9 percent poverty rate.